Time and Place: Donations to the 2025 Boston Mayoral Campaigns

Boston's mayoral elections are coming up soon this fall. What can the financial campaign support of the two main candidates tell us? What trends are present in donation amounts, frequency, and location? Who might have a greater support base to win it all?

Introduction

Boston’s mayoral election is coming up this fall with the preliminary municipal election on September 9th and the general election this November 4th. One critical, yet sometimes overlooked, variable to consider in analyzing the influence of candidates is campaign fundraising: a clear metric to glean further insight into a candidate’s support base.

Campaign finance is a crucial part of any election. It allows us to see who really supports these candidates and how broad or narrow their support is from an economic, political, and geographic lens.

This article will analyze campaign finance data up to August 15. We also examined where the contributions came from, how donations changed over time, and the frequency of donations. The two main Boston mayoral candidates are Michelle Wu and Josh Kraft. Michelle Wu is the first person of color to serve as Mayor of Boston and a former member of the Boston City Council. Josh Kraft is a nonprofit executive and was previously the Chief Executive Officer of the Boys and Girls Club’s Boston chapter. Our analysis highlights the contrast between Kraft and Wu’s approach to this election.

Donations and Donors

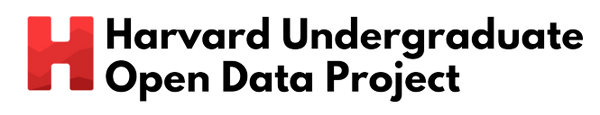

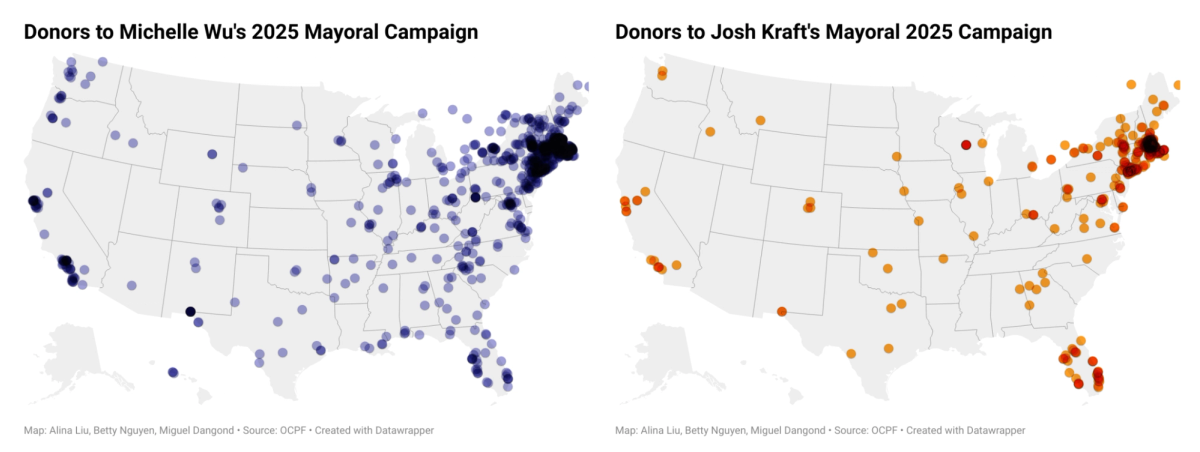

When looking at the distribution of donor geography, there is a sharp contrast between the two main candidates, Wu and Kraft. By August 15th, Wu had raised more than $1.62 million from over 14,000 donors. Roughly 45% of her contributions came from Boston residents, indicating there is broad and widespread local support.

Fig. 1: Number of donations received by mayoral candidates Wu and Kraft as of 08/15/2025

Fig. 1: Number of donations received by mayoral candidates Wu and Kraft as of 08/15/2025On the other hand, Kraft raised $1.35 million from over 2,100 donors, which suggests there are significantly fewer people giving larger amounts of money. Only 29% of his donations came from donors within Boston. The remainder of donations came from out-of-city supporters.

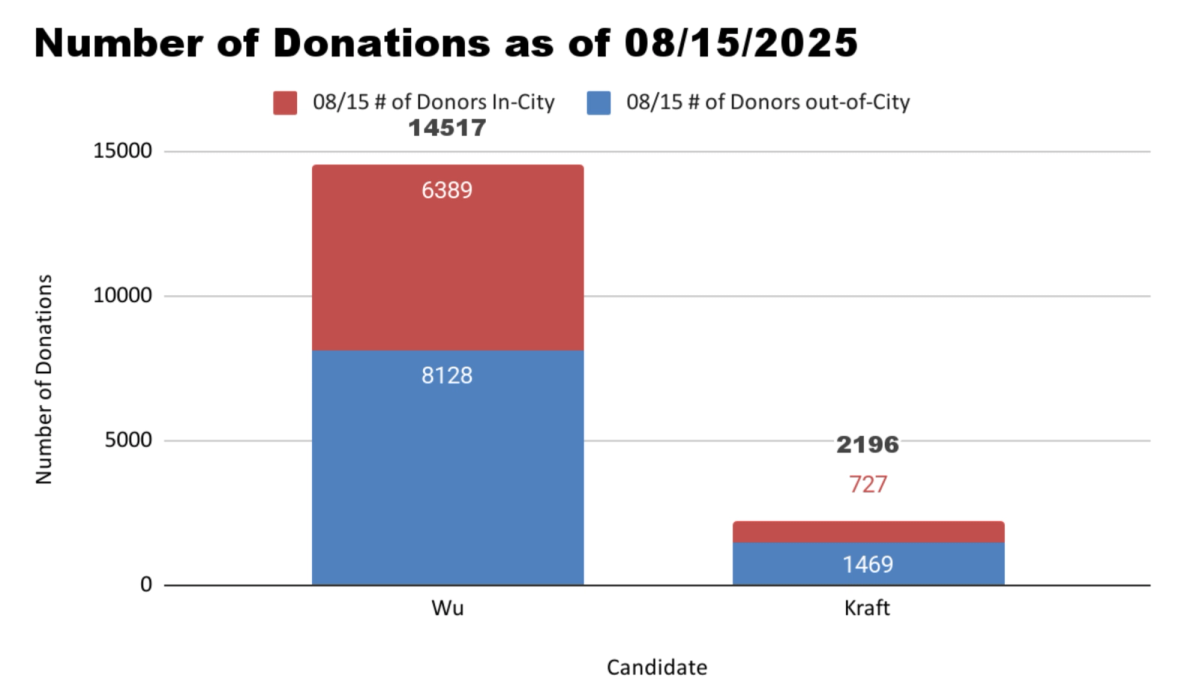

Additionally, Kraft donated $2 million of his own money to his campaign. This donation may be significant toward funding ad campaigns, but does not necessarily reflect how much public economic or political support he is receiving.

Fig. 2: Amount of total donations received as of 08/15/2025

Fig. 2: Amount of total donations received as of 08/15/2025Out-of-State Donations

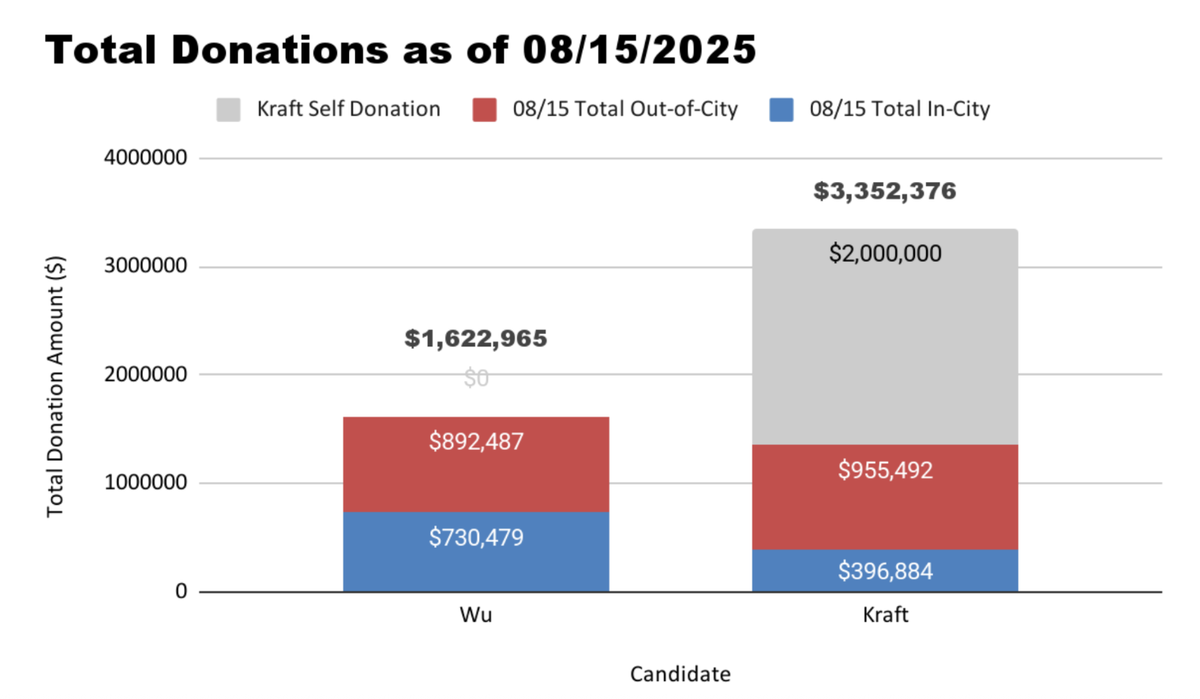

Below is a chart showing the number of out-of-state donations made to both Wu and Kraft each month:

Fig. 3: Number of monthly out-of-state donations

Fig. 3: Number of monthly out-of-state donations

Evidently, the two campaigns experienced a notable spike in out-of-state donations during March. This phenomenon could be attributed to the ongoing dispute between the Trump administration and sanctuary jurisdictions in the US.

Boston is one of many sanctuary jurisdictions that protects American immigrants from detainment. The Trump administration, however, in their efforts to reduce illegal immigration, have been imposing federal funding threats to major cities. He’s been successful in encouraging cities like Louisville to drop their sanctuary status, but others like Boston are fighting back.

Wu testified on the city’s sanctuary policies on March 5th, 2025 before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. She defended undocumented immigrants living in Boston, claiming they deserved to be healthy and safe while living in the city. Kraft has also expressed support towards Boston’s current beliefs on treating immigrants.

Below are maps showing the locations of donors for both campaigns across the US. Darker shades means more donations given.

Fig. 4: Map depicting the location of Boston mayoral campaign donors across the US

Fig. 4: Map depicting the location of Boston mayoral campaign donors across the US

These maps reveal that, outside of Boston, there are plenty of donors supporting both Wu and Kraft’s campaigns. They extend far beyond the local area and reach into the opposite corners of the US.

But there’s an unusual trend regarding these graphs – for both campaigns, donors are distributed very similarly across the US. Plenty of contributors are concentrated in the Northeast for instance, with many living near Boston. There is also a decent amount of supporters dispersed between the Midwest and South, with strong representation coming in from California and Florida.

Most of the aforementioned regions, including California, the Northeast, and the Midwest, are highly concentrated with sanctuary areas. Others, like Florida and the Southern US, have large immigrant populations that support sanctuary policies.

Donating to candidates who support sanctuary policies makes sure that they stay in place. This is particularly important in Boston because of this city’s influence as one of the largest sanctuary cities.

Donation Frequency in Boston

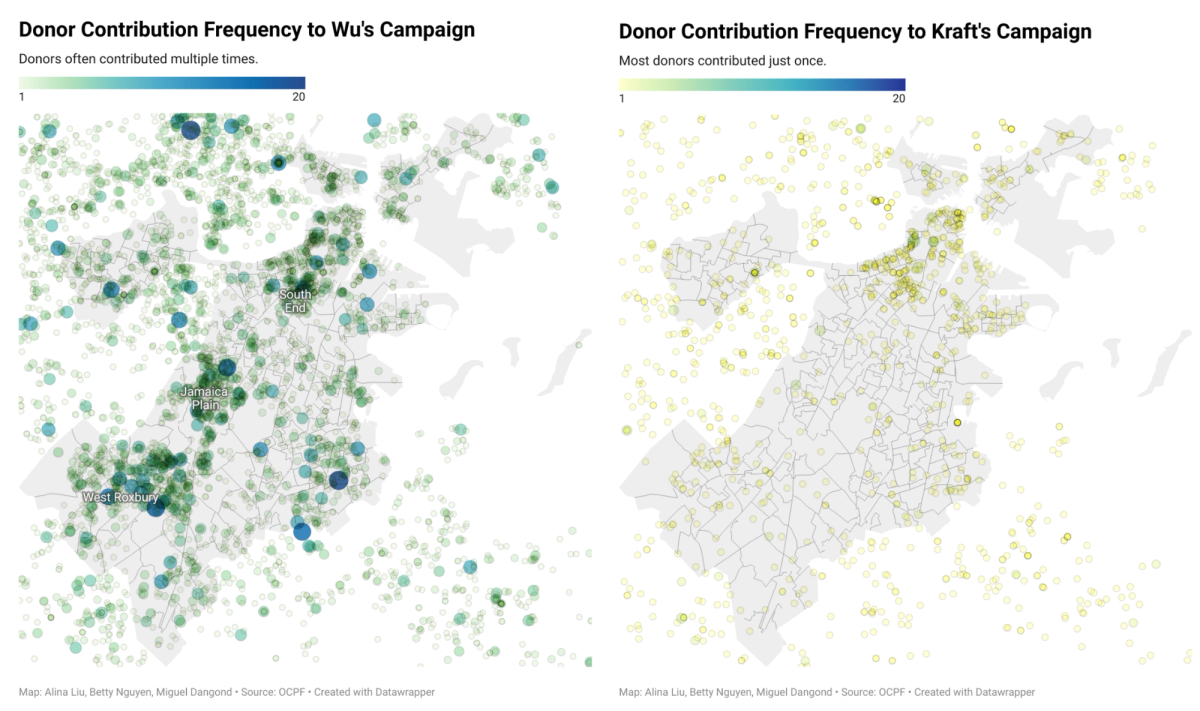

Let’s now zoom into Boston. Within the Boston electoral precinct, it is not unusual for individuals to make more than one donation. Below are maps that show how frequently donors in and near the area have contributed to both campaigns:

Fig. 5: Map of frequency of campaign donations within Boston

Fig. 5: Map of frequency of campaign donations within Boston

In the case of Kraft, donors contribute very infrequently and are primarily concentrated in Northern Boston, a high-income region. But Michelle’s case is different; her campaign has reached far more donors. In addition to her campaign reaching more donors as shown from previous graphs above, these donors are more spread out across Boston and typically donate multiple times. In particular, the neighborhoods of West Roxbury, Jamaica Plain, and South End see a higher frequency of contributions per donor.

This disparity in donation frequency could be attributed to the platforms candidates receive donations from. On one hand, Josh uses NGP VAN, a technology provider for democratic political campaigns. Its user interface for donating is simple: you select the amount you want to donate, provide your payment information, and you’re done! Wu, on the other hand, uses ActBlue—a similar platform with one major difference. ActBlue, unlike NGP VAN, offers the ability to make monthly donations, with a positively connoted “Yes, count me in!” option, and a negatively connoted “No, donate once” option. By framing monthly donations as better than one-time ones, this feature may discretely encourage users to subscribe to monthly donations.

This feature may be particularly effective in Boston, a city with numerous high-income neighborhoods. For instance, consider the neighborhoods with the highest frequency of donations: West Roxbury, Jamaica Plain, and South End. Their median incomes are $107,405, $102,080, and $100,978 respectively – considerably higher than the city’s overall $81,744 median income. Because individuals in these regions have more expendable income, they may be ultimately more likely to donate or subscribe to campaigns.

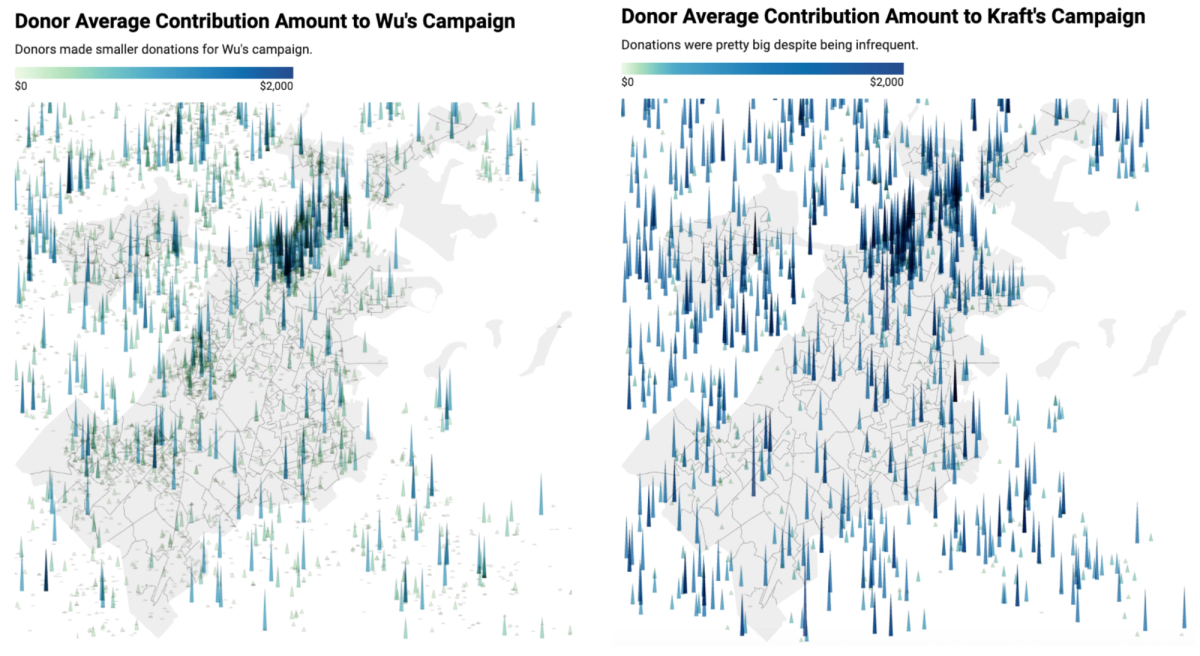

However, it appears that when individuals provide more regular payments, they tend to reduce the amount of money they donate. Below are maps that visualize the average amount of money per contribution supporters have contributed to both campaigns:

Fig. 6: Map of average donation amount to both campaigns per donor within Boston

Fig. 6: Map of average donation amount to both campaigns per donor within BostonThough the maps may look similar at first glance, you may notice that individual donations to Kraft’s campaign tend to be heftier than those made to Wu’s.

Significance

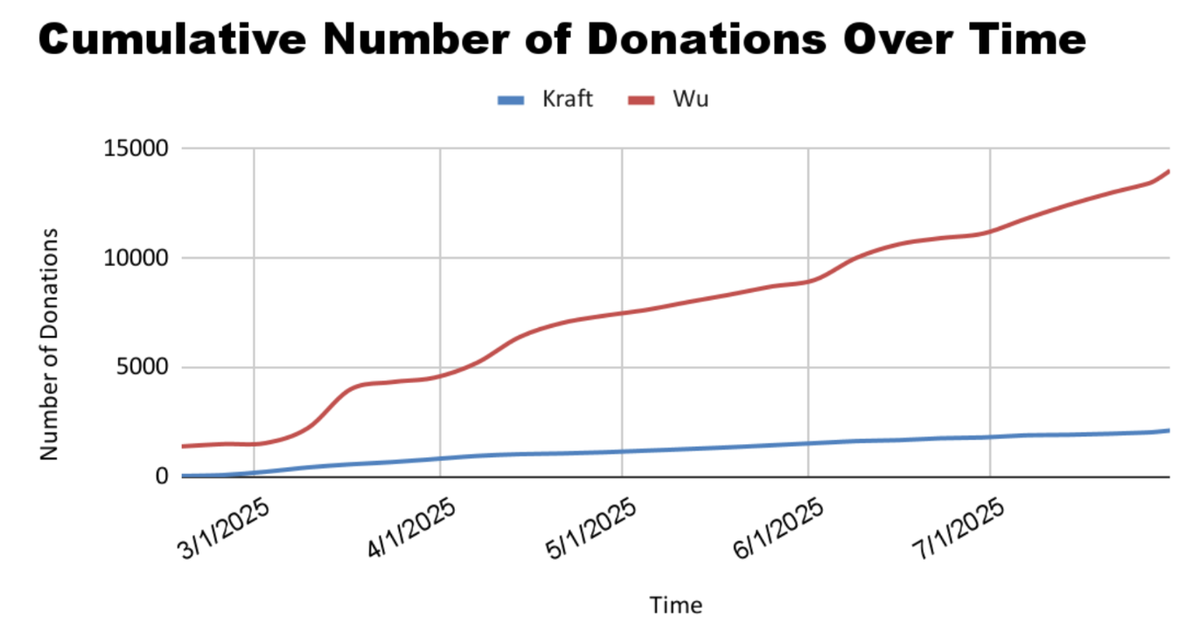

This divide raises the question: why would so many individuals invest so heavily in Boston’s mayoral race? There seems to be a grassroots coalition in the city, versus external influence of wealthier individuals.

Fig. 7: Number of donations received by both campaigns over time

Fig. 7: Number of donations received by both campaigns over timeDonation patterns over time reveal significant differences. The number of Wu’s donors increased steadily with a high frequency of contributions throughout the spring and summer, especially towards the beginning of each month. This trend suggests grassroots engagement since many individuals are coming together in an effort to influence an upcoming election.

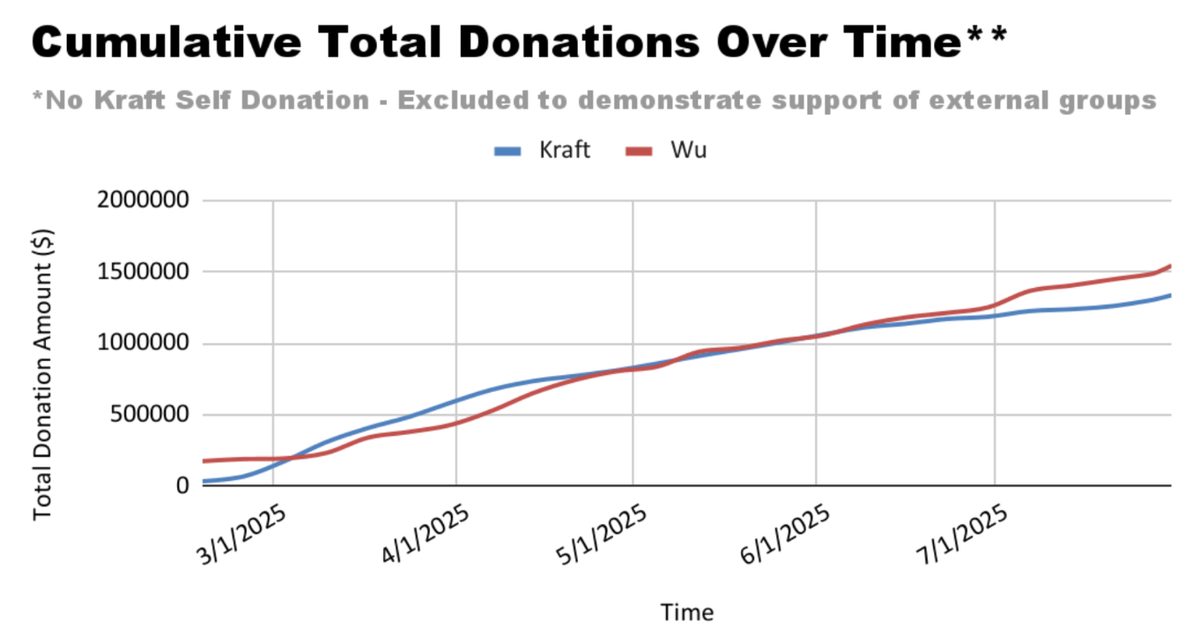

Fig. 8: Total donation amount received by both campaigns over time

Fig. 8: Total donation amount received by both campaigns over timeAnalyzing total donation amount over time, Kraft’s donations also seem to have a consistent and steady pattern. Kraft’s $2 million self-donation was excluded to better visualize the trend of his external donations over time. Notably, even with this large donation, Wu’s campaign still maintained steady contributions during this period—suggesting that Kraft’s spike in donations did not interfere with her grassroots efforts and support.

Over the past 20 years of Boston mayoral elections, the number of donations candidates had by August 15 have been a fairly strong predicator of the election winner (see supplementary figure here). One potential explanation for this is the importance of early contributions. Candidates can use this money to build their platform and connect with voters before election day. Money raised too late in the campaign cannot be used as effectively.

This historical data supports the significance of Wu’s advantage in terms of the number of early donations. Wu’s abundance of donors—together with their persistent support with often multiple donations—by mid-August is a sign of strong support for the upcoming election. Kraft’s reliance on fewer, but wealthier donors, as well as a large amount of self-funding, may not represent the same kind of voter momentum that Wu’s campaign has.

Conclusion

Highlights of the Boston mayoral election demonstrate modern geo-political and economic patterns of the United States. Campaign finance data reveals a lot about a candidate, what they stand for, and possible future outcomes. By investigating the frequency of donations on both the national and local scale, we better understand potential differences between who supports Wu and who supports Kraft. While Wu’s campaign appears to be backed by grassroots donors, Kraft relies on wealthy out-of-city supporters as well as his own personal financial resources.

Even with the $2 million self-donation, past Boston mayoral elections have shown that donor frequency and breadth can predict political success. Money is, of course, critical for driving campaigns and policies, but historical trends suggest that power and leadership doesn’t always come from giant checks, but perhaps from thousands of smaller ones. However, with a political landscape so rapidly evolving, we will just have to see what happens this November 4th.