Passion or Profit: The Harvard Experience’s Impact on Student Interests

How does Harvard affect what vocations and extracurriculars students choose to pursue?

Harvard’s been branded as a pre-professional pipeline that funnels students into careers such as Medicine, Law, Finance, Consulting, and Business. We want to see if the culture of Harvard really does have an influence in transforming people’s interests from high school to college. Specifically, how does Harvard affect what vocations and extracurriculars students choose to pursue?

Introduction

Picasso Van Gogh concentrates in Art History. Well, he used to. Once obsessed with the makings of Ceramics as an outlet for self-expression, he is now Art History turned Economics, zombie-ing over Excel on the nine-to-nine. Is Picasso a one-in-a-million student allured by the spreadsheets of Investment Banking, or is he one of many who find themselves pursuing a means to an end?

Data

We took it upon ourselves to collect, analyze, and report the data on the incentives of selecting concentrations and extracurriculars at Harvard. HODP sent Harvard students a survey to see how many of them followed Picasso Van Gogh down a pre-professional track, and we visualized the data using Plotly and Python. The survey asked questions about students’ motivations behind pursuing their concentrations. In total, 64 participants filled out the survey, including 10 participants from the Class of ‘22, 9 from the Class of ‘23, 31 from the Class of ‘24, 12 from the Class of ‘25, and 2 unspecified students.

Academic Trends

Figure 1: Survey respondents’ distribution of high school activities compared to their distribution of college activities.

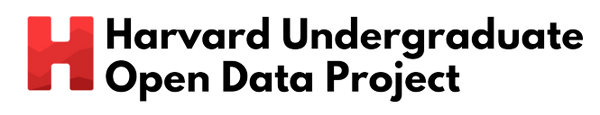

Figure 1: Survey respondents’ distribution of high school activities compared to their distribution of college activities. To determine how Harvard affects the academic interests of students, we asked our survey respondents for their intended concentrations on their Harvard application versus their declared concentration. According to Business Insider, Harvard’s top three concentrations are Economics, Government, and Computer Science. The sharp increase in computer science concentrators in Figure 1 reflects this statistic, but the number of government and economics concentrators decreased. However, many of the joint concentrations also included computer science (3 respondents), government (5 respondents), or economics (4 respondents) as one of their joint fields, making these decreases less drastic than they appear. Therefore, while Harvard does seem to lure students into this trifecta, students likely combine one of these fields with their original interests rather than entirely changing their academic plans.

Figure 2: For students who selected their concentration because of “money,” this visual reports if they are in pre-professional clubs.

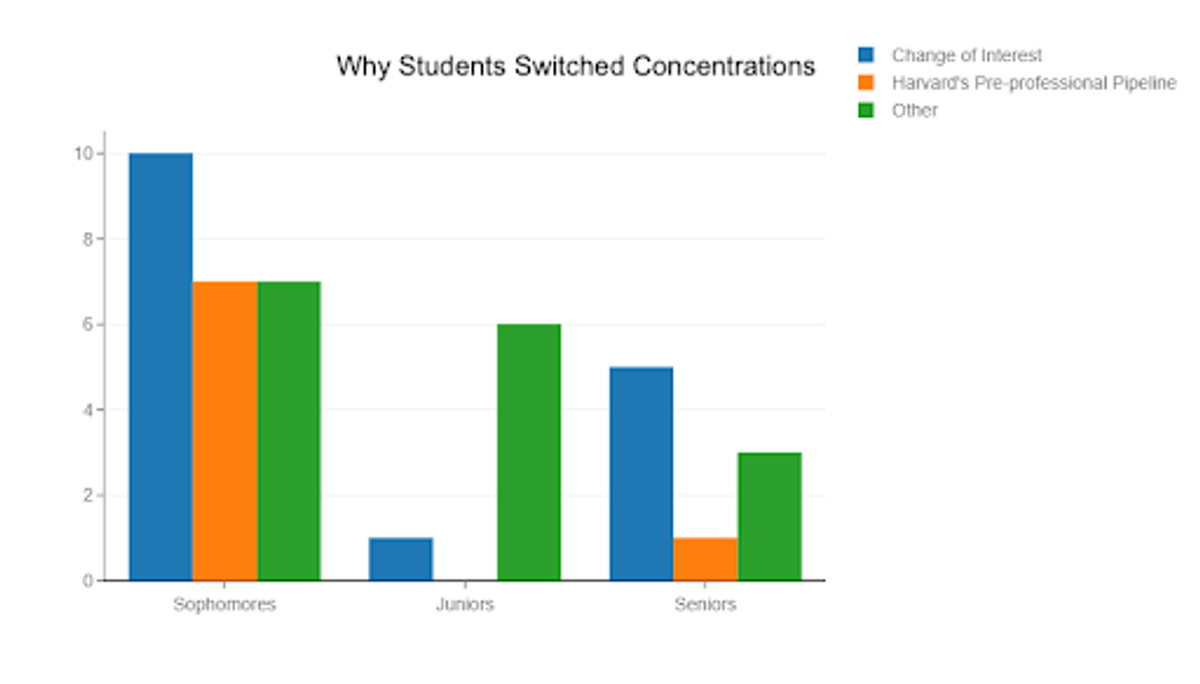

Figure 2: For students who selected their concentration because of “money,” this visual reports if they are in pre-professional clubs.  Figure 3: Reasons why students switched concentrations broken down by their class. “Other” refers to reasons such as family pressure, clout, and peers.

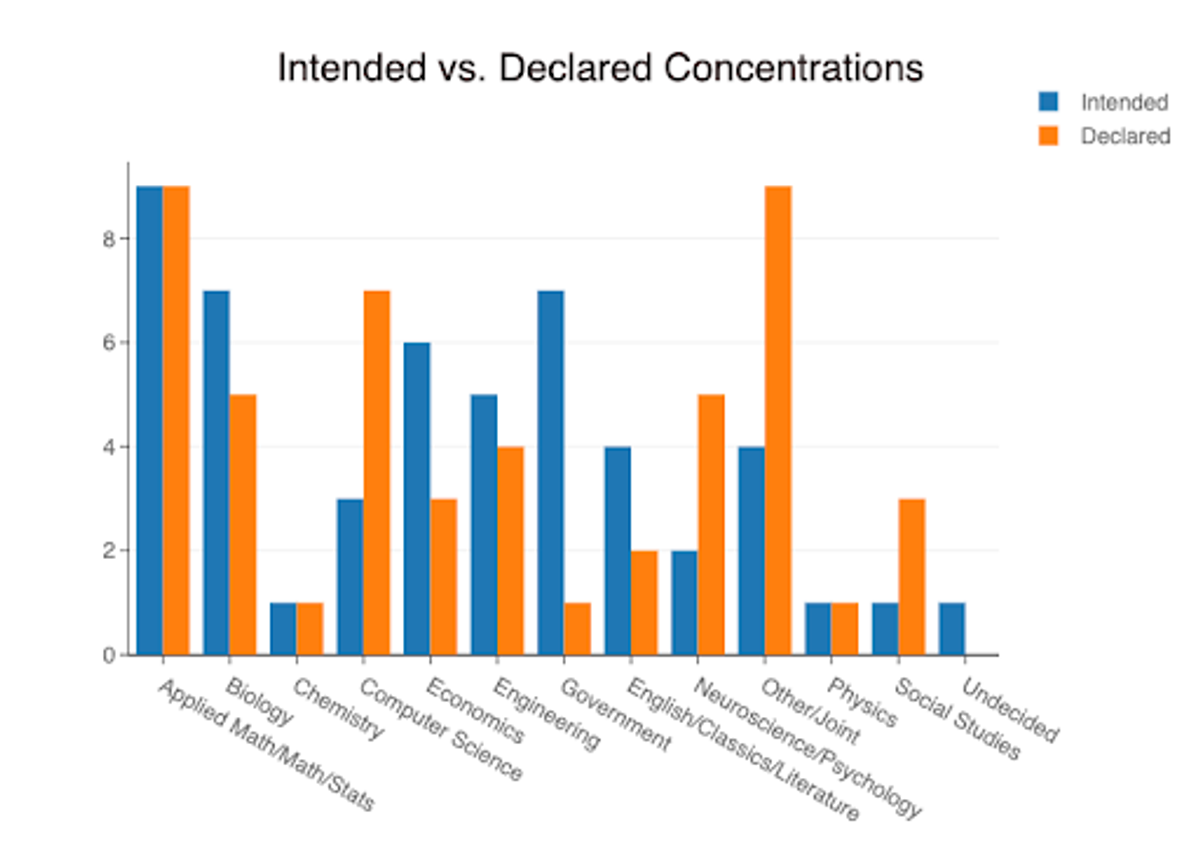

Figure 3: Reasons why students switched concentrations broken down by their class. “Other” refers to reasons such as family pressure, clout, and peers.Furthermore, just like Picasso Van Gogh, the majority of Harvard students deviate from original intentions when applying to university. Although Harvard’s “pre-professional pipeline” does affect students’ ultimate concentration, especially for students in the Class of ‘24, changes in passion are reported to influence their decision to change concentrations the most. In addition, extraneous factors such as family and social pressure are also more significant than the pre-professional pipeline in determining students’ decisions. It’s possible that the opportunities and the culture at Harvard are part of the reason why students’ interests change, but ultimately their love for a particular subject plays the greatest role.

Extracurricular Trends

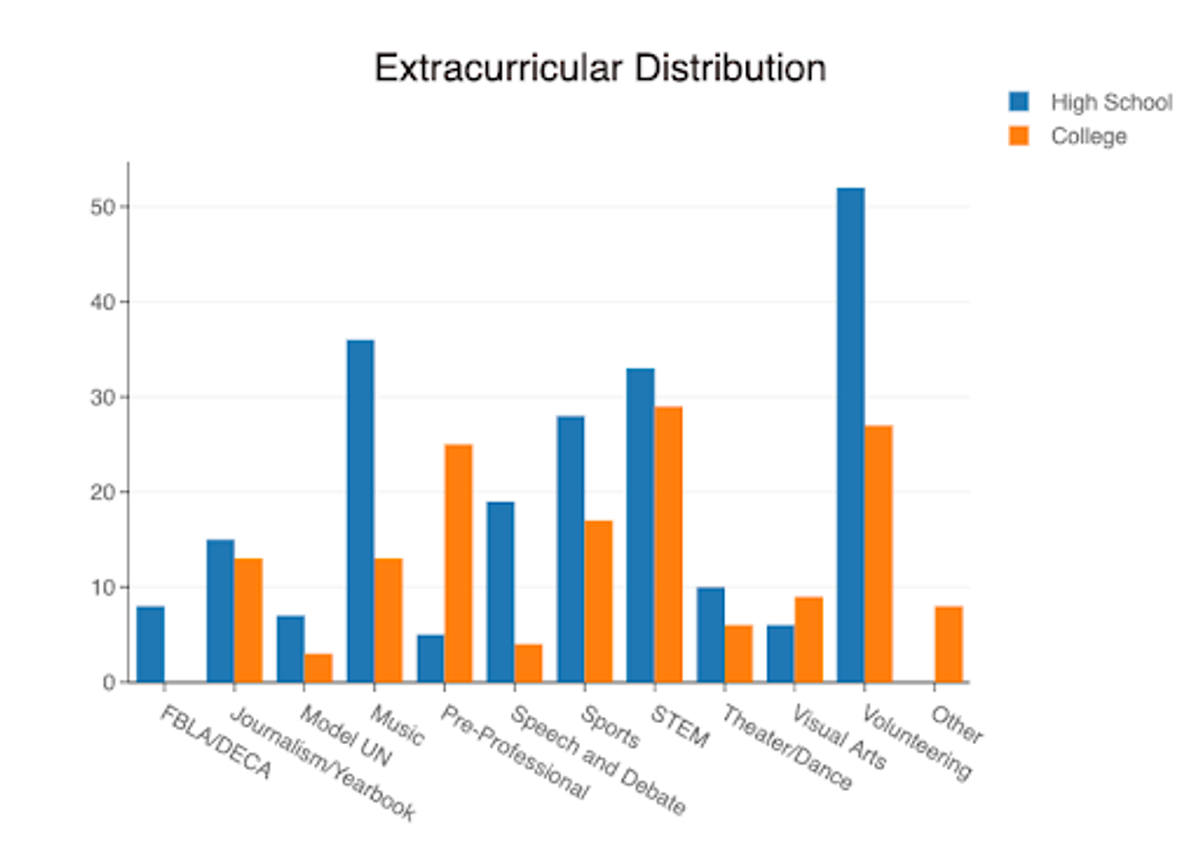

Figure 4: Survey respondents’ distribution of high school activities compared to their distribution of college activities.

Figure 4: Survey respondents’ distribution of high school activities compared to their distribution of college activities.Next, we asked our respondents about their extracurriculars in college versus high school. Overall, there is a general decrease in involvement with clubs in college; however, extra-curricular interest is far more indicative of Harvard’s pre-professional focus. As seen in Figure 4, there is a noticeable increase in involvement with pre-professional clubs in college. In fact, only the visual arts and pre-professional groups saw an increase in engagement. Service-oriented extracurriculars such as volunteering saw a significant decrease compared to high school. Likewise, extracurricular activities focusing on the refinement of specific skills, like music and speech, saw a noticeable decrease in involvement. STEM-related activities saw a small decrease, staying relatively constant compared to other extracurriculars. These trends suggest that Harvard’s pre-professional culture plays a significant role in how students spend their time out of classes. Through their extracurriculars, respondents indicate that they are positioning themselves for STEM-related or business-oriented careers, rather than service-oriented jobs.

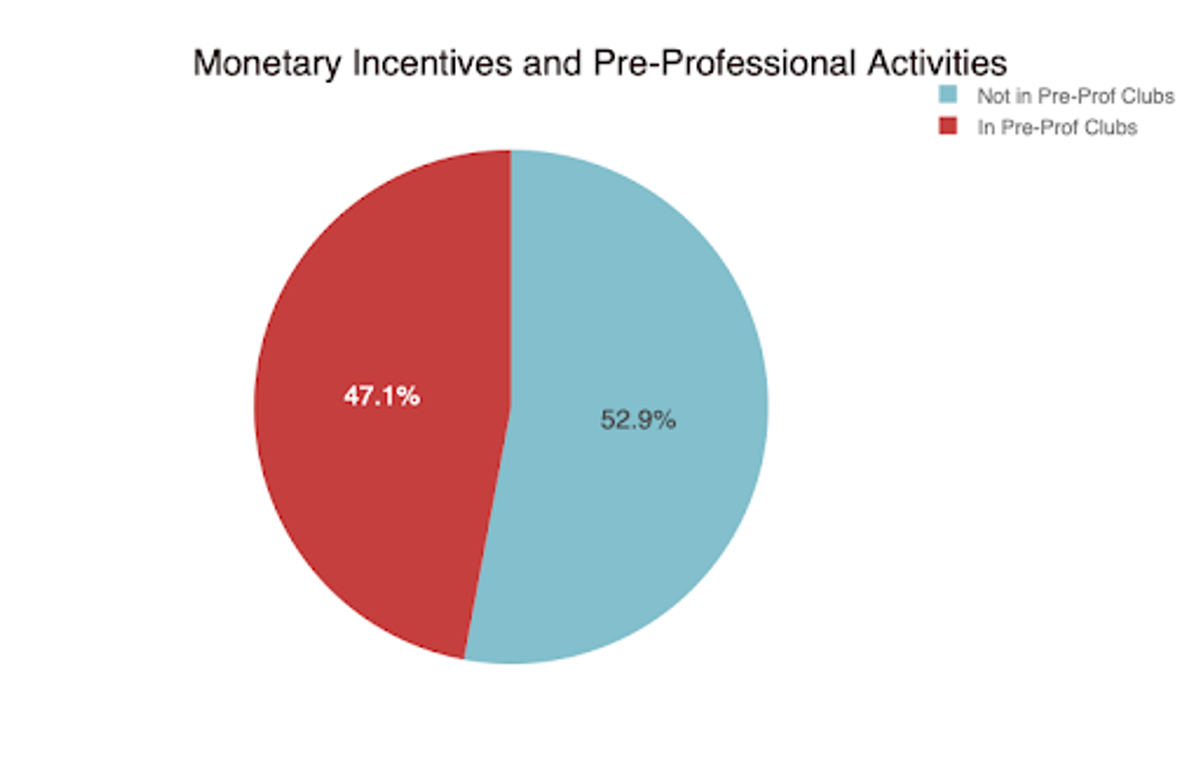

Figure 5: For students who selected their concentration because of “money,” this visual reports if they are in pre-professional clubs.

Figure 5: For students who selected their concentration because of “money,” this visual reports if they are in pre-professional clubs.Additionally, we wanted to gauge how much extracurricular involvement in pre-professional clubs stemmed from monetary incentives, especially amongst those who selected financial incentives to be the primary reason for switching their concentration. Figure 5 indicates that a majority of individuals who switched their concentration due to monetary incentives are involved in pre-professional clubs. This suggests that members believe pre-professional clubs offer a competitive edge over the rest of their peers on paper, especially considering that these clubs market themselves to be career and network boosters.

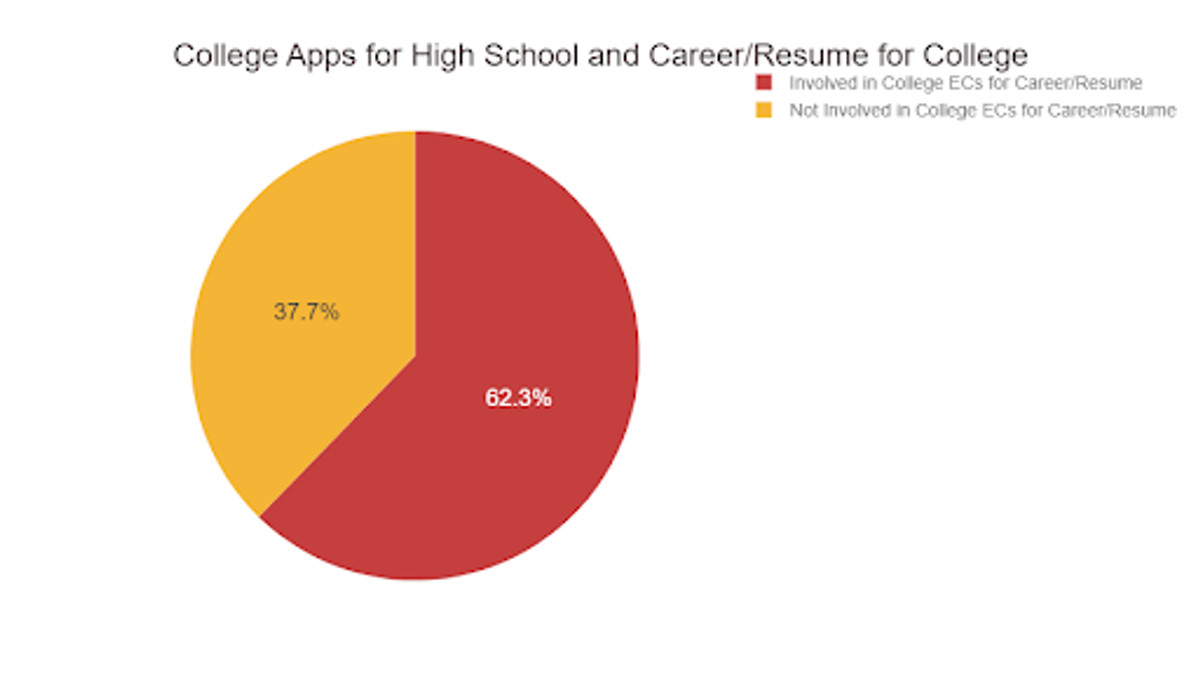

Figure 6: For students who selected their high school extracurriculars because of “college applications,” this visual showcases if they chose college extracurriculars to boost their career and resume.

Figure 6: For students who selected their high school extracurriculars because of “college applications,” this visual showcases if they chose college extracurriculars to boost their career and resume.Lastly, we wanted to examine the prevalence of “resume building” in college, specifically focusing on those who practiced it in high school. Figure 6 shows that just under two-thirds of those who practice resume building in high school have continued to do so in college. With the strong increase of pre-professional involvement shown in Figure 4 in mind, Figure 6 suggests that a majority of students join pre-professional clubs as a means of resume building. These findings are indicative of Harvard’s pre-professional culture, as many students continue to structure their free time around career development and resume enhancement.

Conclusion

So is the Picasso Van Gogh archetype as commonplace as one may think? Our data suggests that Harvard’s culture pushes students to prioritize career and resume building, particularly in how students choose to spend their time outside of the classroom. At the same time, our sample size is fairly small compared to the overall Harvard undergraduate population, so our results could be skewed by the self-selection of the type of students who are more inclined to fill out a HODP survey. We’re curious about how Harvard and its students will evolve to the rest of the world, so stay tuned!

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Matthew Qu, Ethan Lee, Patrick Song, Ian Espy, Isheka Agarwal, and the rest of the HODP community for supporting us every step of the way!

Code Excerpts