Go HAM on Art: A Look at Cultural Representation in the Harvard Art Museums

How culturally diverse is the Harvard Art Museums' collection?

Introduction

Harvard is lucky to house 13 museums on its campus, but perhaps the one most familiar to students is just a stone’s throw away from Annenberg: the Harvard Art Museums (HAM).

Composed of three museums, HAM organizes public education and teaching programs, supports research endeavors, and collaborates with campus, community, and global partners to serve students, scholars, and families alike. HAM's collection guides how its audience perceives different cultural histories, and shapes the scholarship in art history, conservation science, and other fields that this institution produces. So, citing HAM’s mission to “bring to light the intrinsic power of art and promote critical looking and thinking,” we considered: how culturally diverse is HAM's collection?

Methodology

We decided to investigate which cultures are more represented at HAM by analyzing a random sample of 15,000 art objects in their collection, leveraging their open source API. We focused on each piece’s views, rank, and culture as categorized by HAM. Due to the large number of cultures as well as in an effort to reduce the noise of the random sample, we listed cultures with less than 500 pieces in our sample as “Other.” A piece’s views is how many unique page views it received on HAM’s website. The rank of a piece is an internal measure calculated by HAM to order search results, where a lower rank corresponds to more recent activity. All code and data are at our GitHub.

Analysis

Which cultures are most represented?

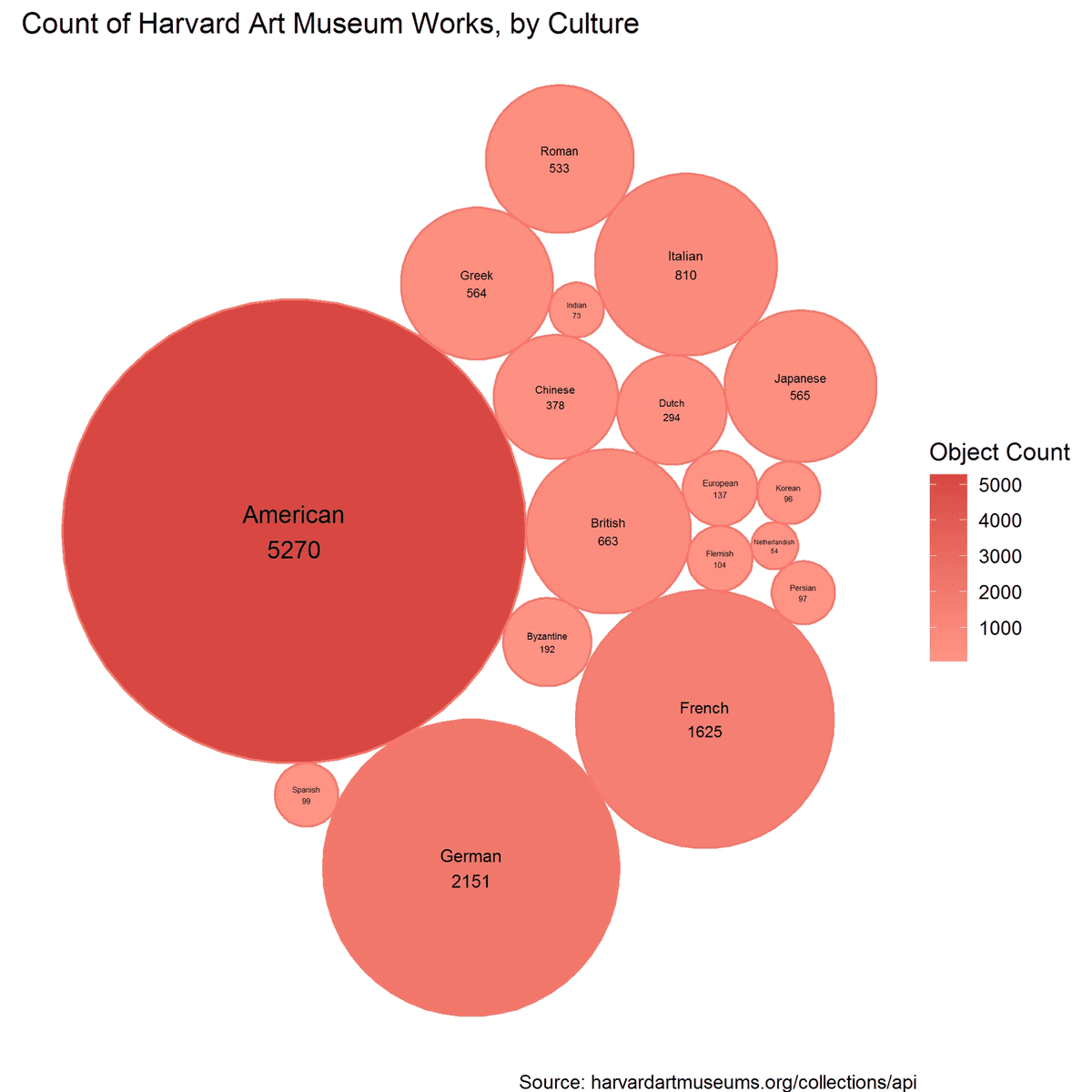

A circle plot of the number of pieces per culture in our sample.

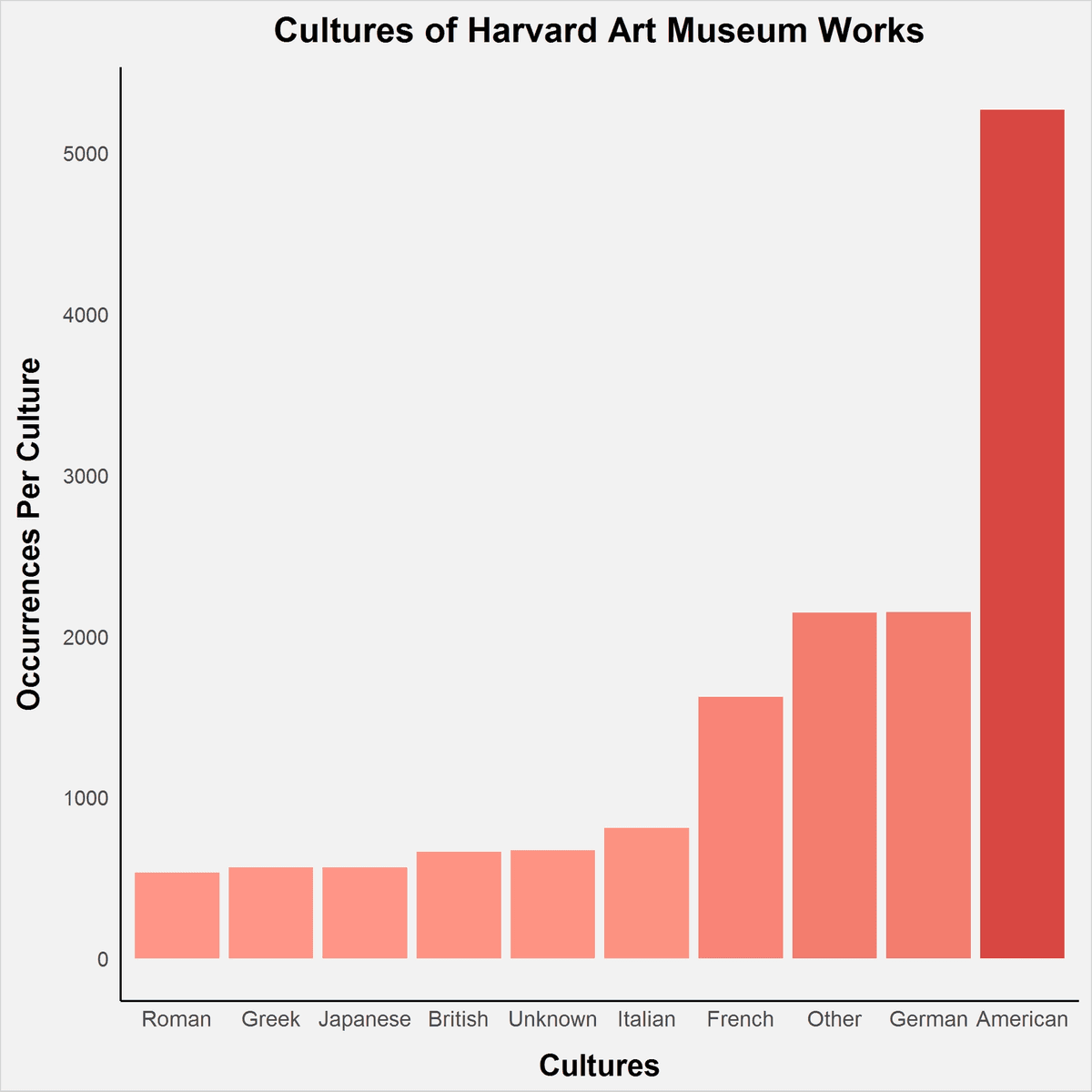

A circle plot of the number of pieces per culture in our sample. A barplot of the number of pieces per culture in our sample.

A barplot of the number of pieces per culture in our sample.Aggregating the occurrences of the top cultures, we see that most of the art is American: this is unsurprising, because a primary way HAM expands its collection is through mostly American donors. The collection contains art from mainly Western cultures, with German, French, Italian, British, Greek, and Roman art also ranking in the top 10. Notably,

— and this mirrors the identity and philosophy of HAM’s three museums. The original Fogg Museum was founded in 1895 for North American art scholarship and Western art preservation, and the Busch-Reisinger Museum was founded 6 years later with an emphasis on German-speaking countries. It was only until 1985 that the Sackler Museum was created for works from Asia, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. Here, the weight towards American and German works and away from non-Western works seems clear.

Which cultures are most viewed online?

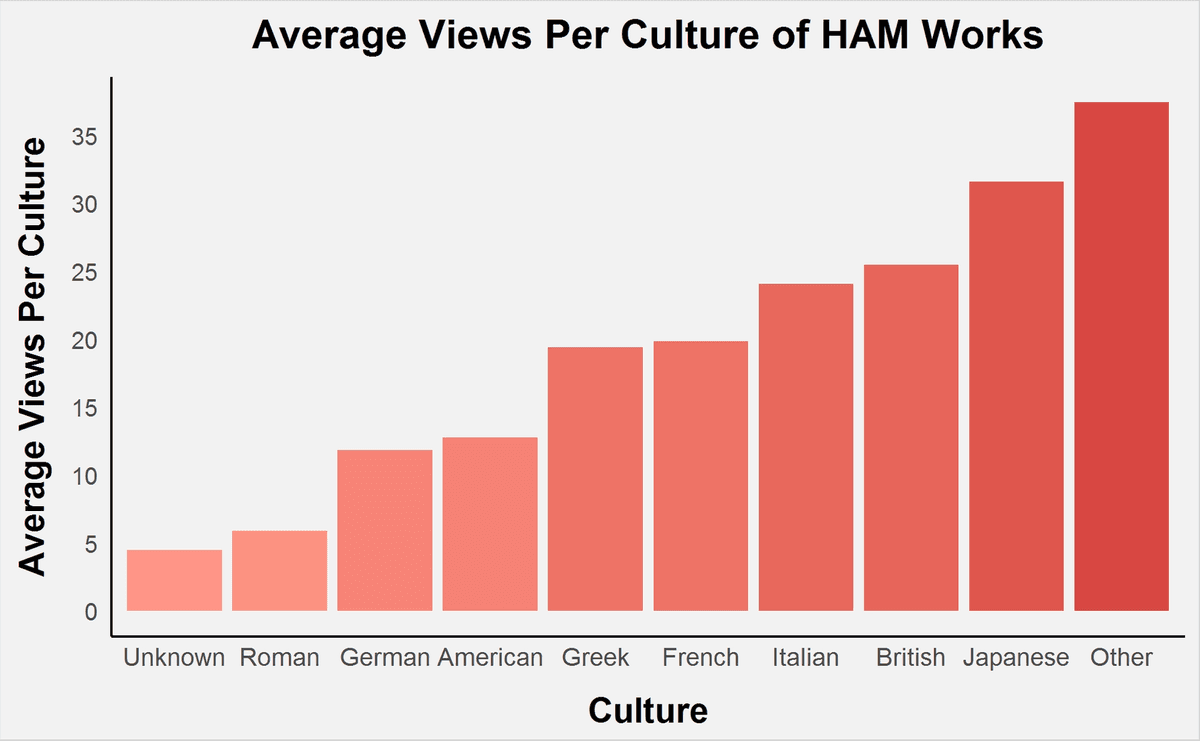

A barplot of different cultures’ average views per piece.

A barplot of different cultures’ average views per piece.Next, we discovered that different cultures have different mean (average) views: our tests indicate at least one pair of cultures whose medians are significantly different. The ranking of views differ from the ranking of occurrences. Even though American art is most represented, it is one of the least viewed. On the other hand,

A possible cause could be the uptick in Japanese exhibitions in recent years, such as “Japan on Paper” in 2019. And, until July 2021, HAM is featuring "Painting Edo," a special exhibition on art from Japan’s early modern area. As the only special exhibition to debut in 2020, and as people sought quarantine-friendly activities, it is possible that the now-online exhibition led to increased views and renewed interest in HAM’s Japanese art collection.

A deeper dive into views

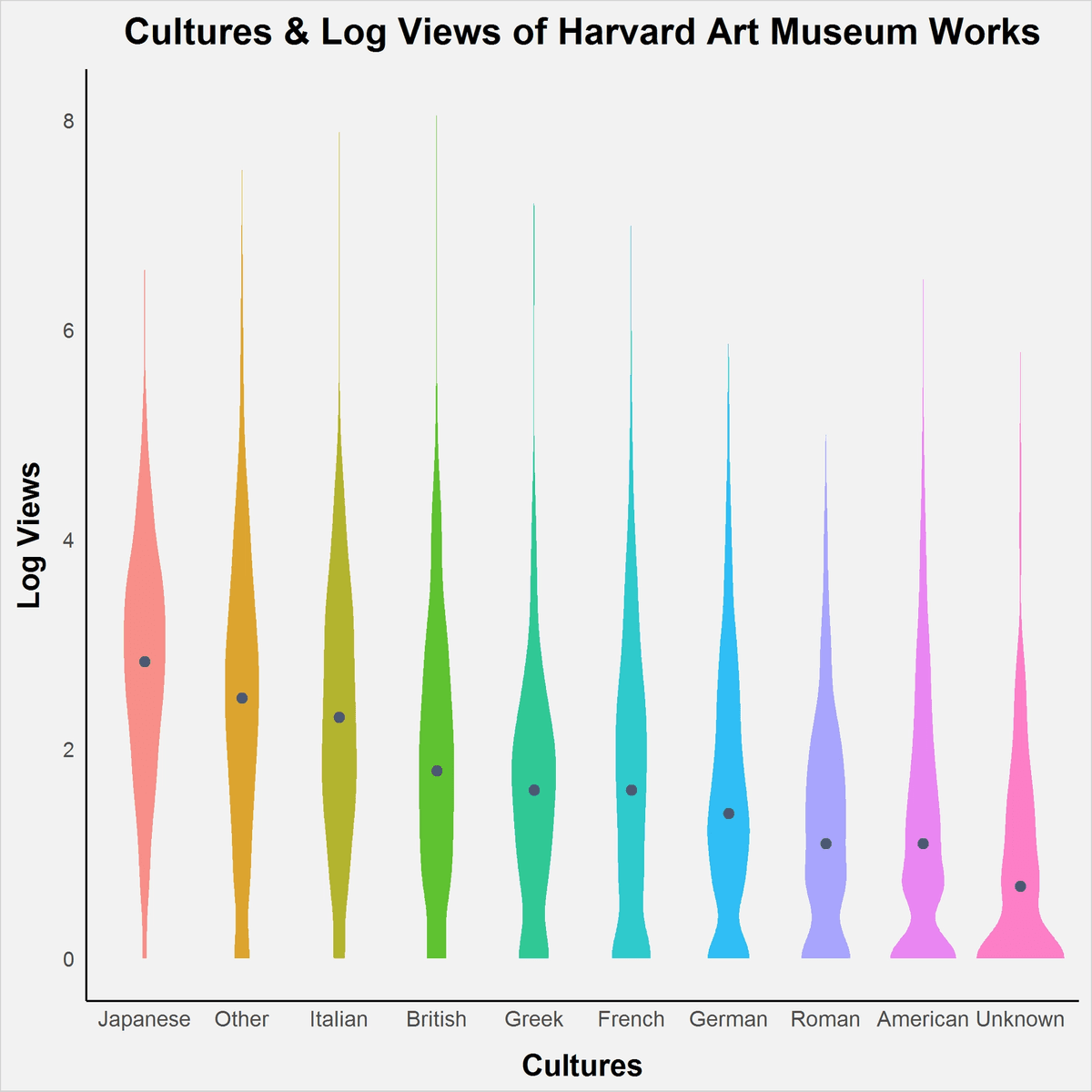

A plot of different cultures’ pieces by log-views.

A plot of different cultures’ pieces by log-views.Here, to minimize the effect of extreme data values, we examine each culture’s distribution and median of log-transformed views, represented by the thickness of each blob and a dot, respectively. We decided to log-transform our views to lessen the effects of extreme values and draw more informative conclusions. As many pieces had zero views, we added a view to each piece so that we are not taking the logarithm of zero. When we compare cultures by their median log-views vs. the previous boxplot’s average views, the order of cultures have shifted: in particular, American art places sixth in mean views, but now places ninth in median log-views, and Japanese art has moved from second to first.

As inferred from the stump on the bottom of the blob,

but its tall tip reveals that some of the most-viewed HAM pieces are American, likely pulling up their mean average views in the previous graph, but resulting in lower median log-views. Similarly, German and Roman art are also plagued by pieces that have not been viewed, which pull their median views down. On the other hand, most Japanese art has been viewed multiple times and has the most consistently distributed views amongst its pieces, as shown by the about-symmetrical blob.

How do HAM works “rank”?

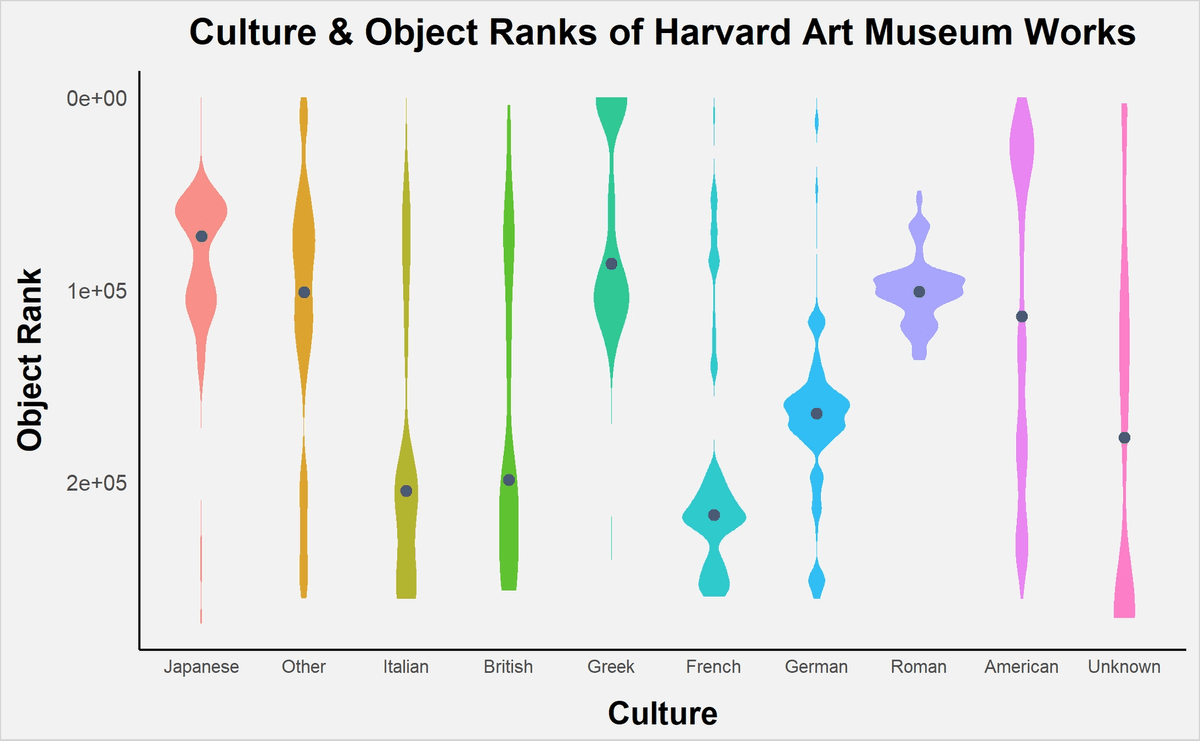

A plot of different cultures’ pieces by rank. The lower the rank, the more popular the piece.

A plot of different cultures’ pieces by rank. The lower the rank, the more popular the piece.The final measure we explore is each piece’s “rank”, an ordinal ranking calculated by HAM to push less-popular pieces, which are assigned a higher rank, to the top of search results. Page views and the last time an object was viewed are factors, but HAM does not reveal the other variables included in this rank. Therefore, we will only interpret rank as a way to measure popularity.

On average, Japanese art tops the ranks, which again suggests that a possible reason for Japanese art’s popularity is due to recent HAM exhibitions. This centralization of higher rank also alludes to the later founding of the Sackler Museum for Asian and other non-Western art in 1985: more of its collection was consolidated in the Internet Age, suggesting a larger proportion of its pieces being documented, discussed, and explored online.

Confirming our observation of American art’s lower average views, while a large portion of American art is popular, a significant number of pieces had worse ranks. Moreover, Greek art has been extremely popular: it has the second-best median rank but places fifth in log-views. There also are two distinct clusters, suggesting that some Greek pieces have been much more popular than others. This pattern contrasts with Roman art, which clusters around a median rank with few outliers: this is perhaps due to consistent but never massive interest in Roman art.

A last point of interest is that

Since these pieces overall are not as thoroughly documented, it is likely they’d have a worse rank due to less photos and immediate relevance, since users more often look up art from a specific place, time, or exhibition.

Conclusion

After investigating the representation and popularity of different cultures in the Harvard Art Museums, we notice its collection significantly veers towards works from American, German, and other Western cultures, which reflects the art interests of its donors and how two of its three sub-museums focus on Western art. American art has the most pieces of any culture, and while average in views, some of the museums’ most popular works are American.

Japanese art stands out as the only non-Western culture in the top 10 most represented cultures: our data indicates a surge in popularity, in both ranks and views, perhaps due to recent emphasis on the curation of Japanese works. This indicates that despite its Western-heavy beginnings, the Harvard Art Museums can indeed diversify its offerings. They can search for donors and partners with expertise in other art domains, implement art discovery features to make uncategorized works more visible, and make space for art that did not have a sufficient platform in the existing museum structure, such as their new “Modeling African Design” exhibition. In turn, the Harvard Art Museums can cultivate a more global and dynamic understanding of what “art” is, and further their mission to genuinely “advance knowledge about and appreciation of art and art museums.”

You can check out the data used for this analysis here.