Gender Disparity in Harvard Faculty

Using data to unearth the pervasive gender imbalance within Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

We know there are gender inequities everywhere — we’re constantly hearing about the underrepresentation of women in STEM and the poor treatment of women in the tech industry and on Wall Street. Recently, The Crimson highlighted the struggle of being a woman in the Harvard math department, which has no senior female faculty. At the Harvard Open Data Project, we decided to dig deeper into this data to see how Harvard is really doing with gender balance.

Data collection methods

We counted the faculty listed on each department’s website and identified their genders based on pronouns used in their biography. When we use the word “female” or “women” in this article, we refer to people who take the “she/her/hers” preferred gender pronouns. If pronouns weren’t present, we found the most recent articles online about the professors and looked for their pronouns there.

Harvard has many types of faculty. In decreasing order of seniority, there are full professors, associate professors, assistant professors, and other faculty (including lecturers, preceptors, adjuncts, and instructors). Full professors are tenured; assistant and associate professors are considered “tenure-track.” We also included professors of the practice, who are fairly senior but not tenure-track. We omitted visiting professors.

Let’s dig into our findings.

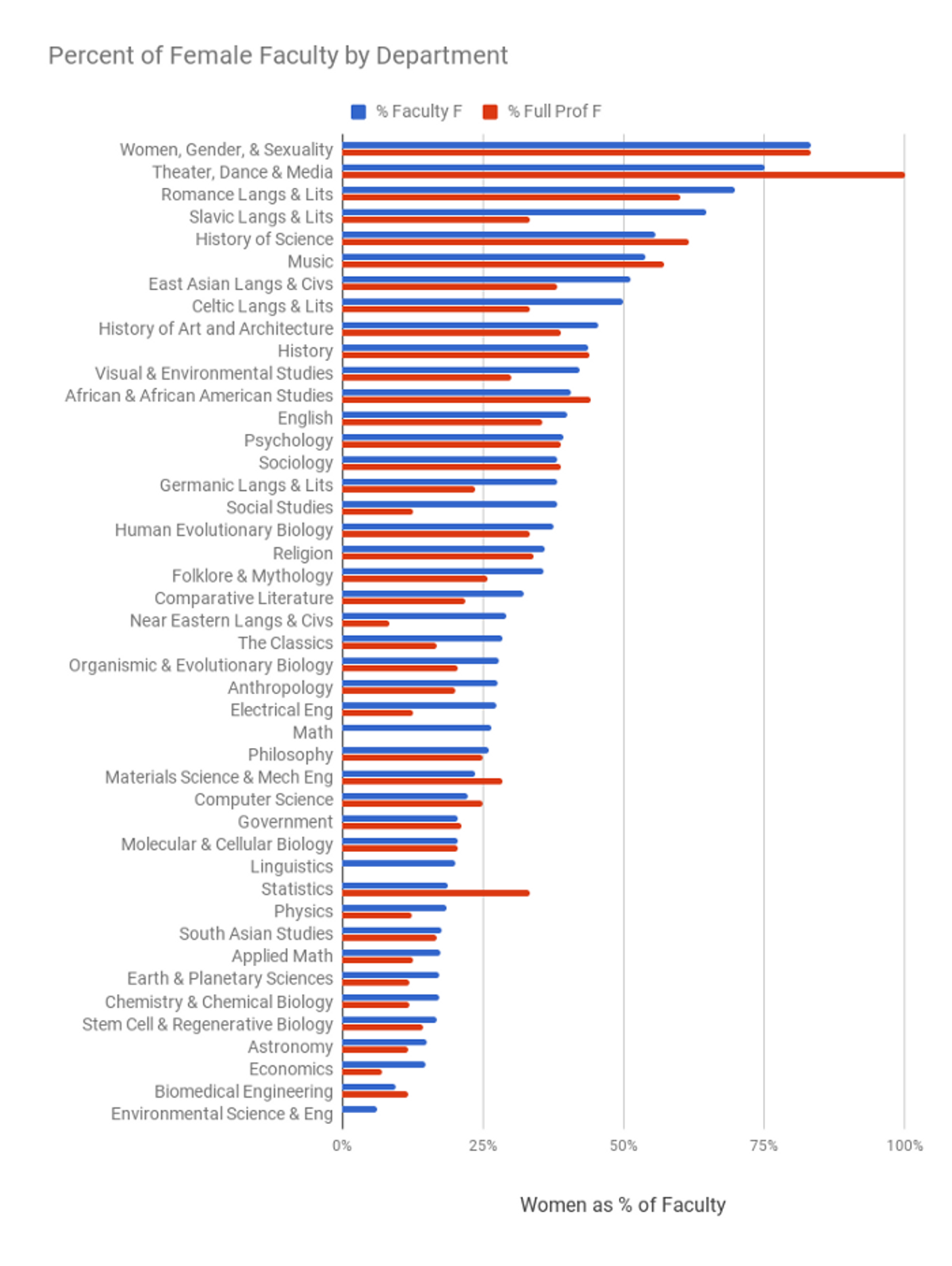

Men dominate the faculty overall

We found that Harvard faculty are overwhelmingly male, even in disciplines one might not “expect.” The departments with the smallest proportion of female faculty are environmental science and engineering (6%), biomedical engineering (10%), and economics (15%), in that order.

Surprisingly, biomedical and environmental engineering are more than 15% lower than the more stereotypically male-dominated electrical and mechanical engineering departments. Only seven departments have more female than male faculty: Women, Gender, and Sexuality (83%); Theatre, Dance, and Media (75%); Romance Languages and Literatures (70%); Slavic Languages and Literature (65%); History of Science (56%); Music (54%); and East Asian Languages and Civilizations (51%).

Curious to know how your favorite departments stacked up? Check out our graph below.

Gender disparity worsens among full professors

If we narrow our consideration to just tenured faculty (i.e. full professors), we find an even starker disparity. Tenured faculty are even more overwhelmingly male than faculty overall.

Several language departments have a majority of women among their faculty overall, but only a minority of women among full professors. For example, Slavic Languages and Literature drops from 65% (female faculty overall) to 33% (female full professors) and East Asian Languages and Civilizations drops from 51% to 38%. This is probably because these departments have many non-tenured preceptors, who are largely female.

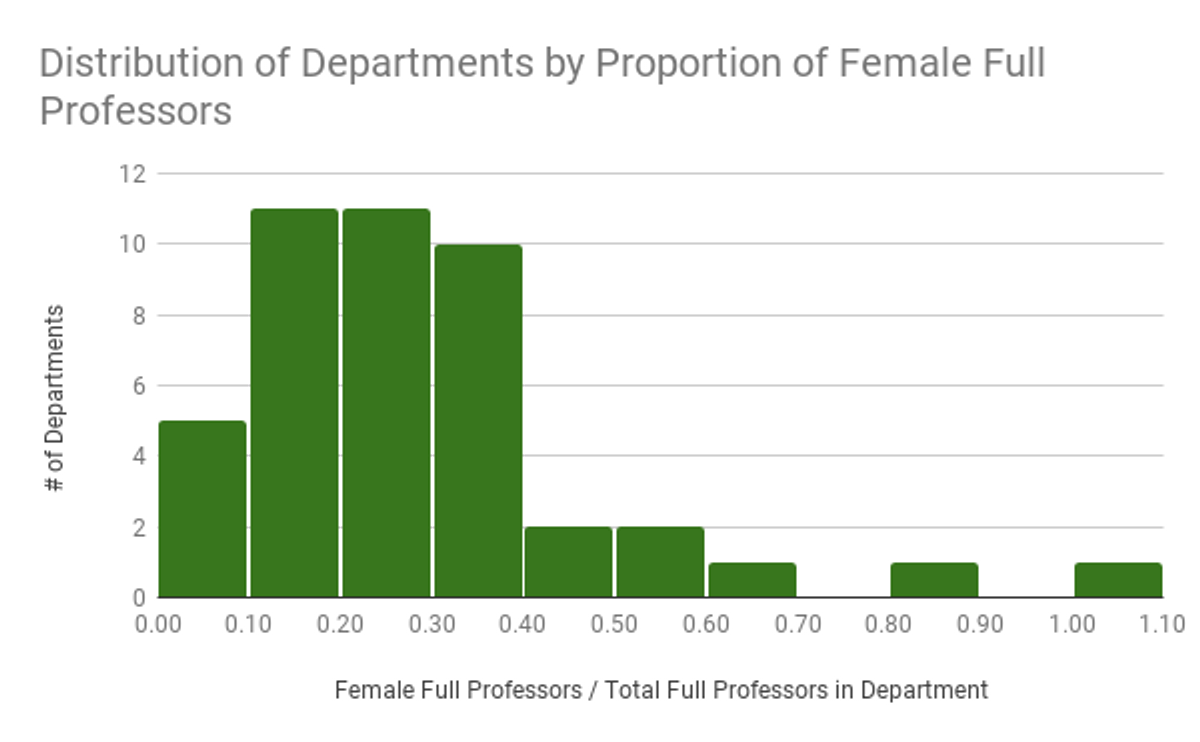

Some bright spots, but overall cause for concern

Due to historic underrepresentation in STEM fields, we might expect STEM departments to have relatively low percentages of full female professors.

These STEM departments fare better than several social sciences and humanities departments like anthropology (17% of full professors are female), classics (17%), social studies (13%), and government (21%). However, it’s important not to overstate this, since — as we’ll see in the next section — SEAS overall has a far smaller proportion of women than the social sciences and humanities.

Interestingly, the statistics, history of science, and computer science departments have higher proportions of female tenured faculty than overall female faculty.

Despite some bright spots, Harvard faculty overall still skews heavily male. There were as many departments with no female tenured faculty as departments with more than 60% female tenured faculty (three departments). 85% of departments have less than 40% female tenured faculty, and only 5 of the 44 departments studied have between 40% and 60% female faculty (what we might consider gender-balanced) — that’s the same as the number of departments with less than 10% female faculty!

More seniority means fewer women

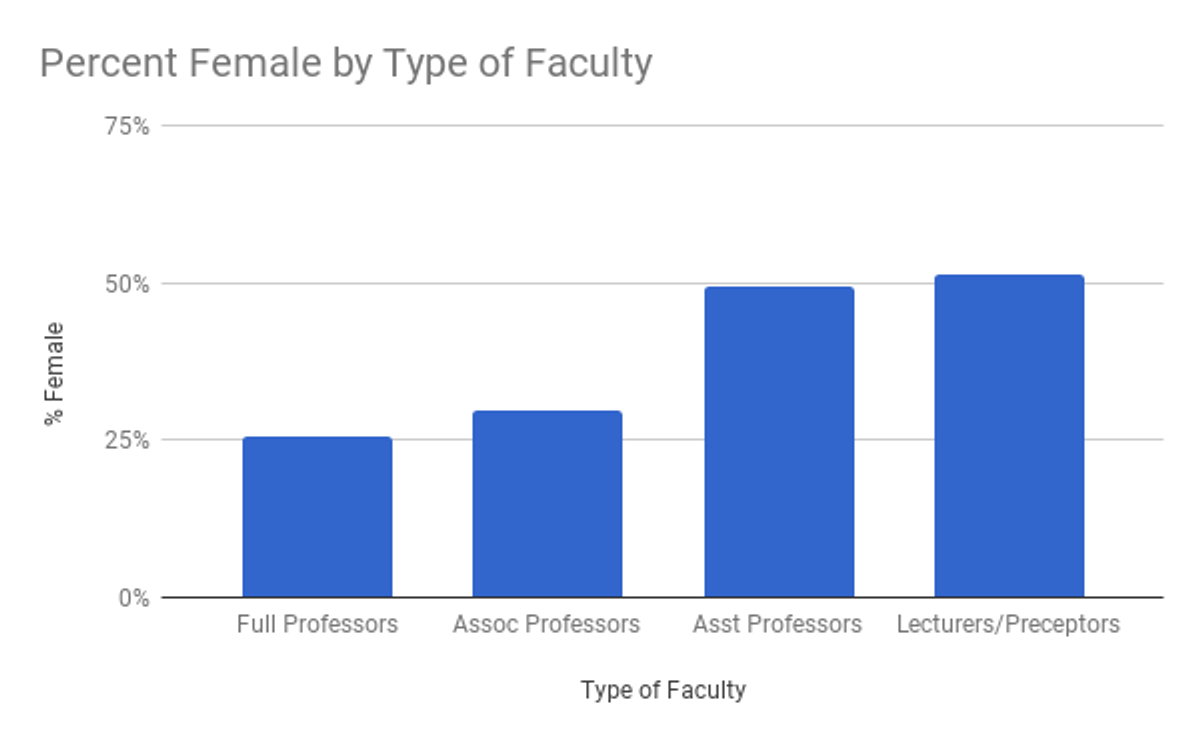

If we look at the percentage of female faculty by type (full professors, associate professors, assistant professors, and lecturers/preceptors), we see an inverse relationship between seniority and percent of female faculty.

Not all Harvard divisions have the same disparity

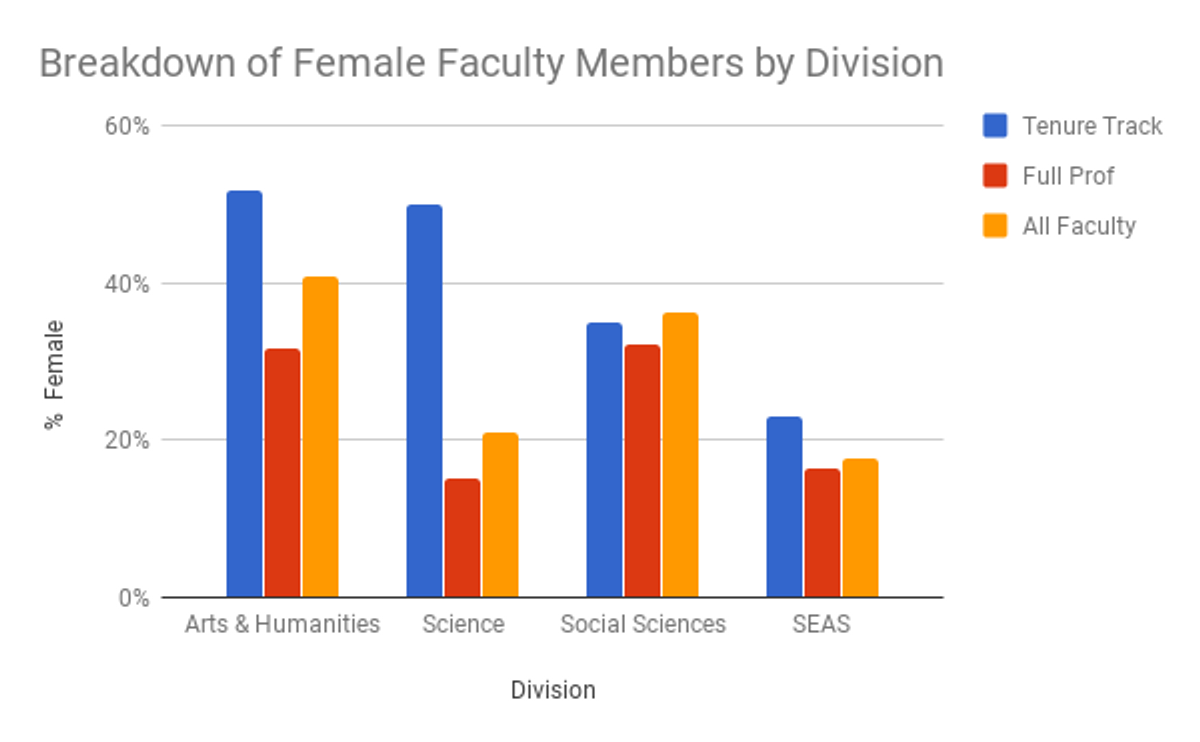

When we group the departments by division, interesting patterns emerge. The social sciences, arts and humanities lead in the percentage of female tenured faculty at 32% each, while SEAS and sciences lag behind at half that (16% and 15%).

Looking at tenure-track faculty (i.e. associate and assistant professors), the percent of women jumps across the board. The arts and humanities and sciences lead, with 52% and 50% respectively, compared with social science and SEAS, at 35% and 23% respectively.

Surprisingly, the sciences have the lowest proportion of female full professors but the highest proportion of female tenure-track positions, while the social sciences and SEAS have similar proportions. This may indicate recognition in the sciences of the gender disparity and an attempt to improve the gender balance with new tenure-track appointments. Another explanation is that female tenure-track faculty aren’t staying or getting promoted to tenure.

It’s probably a combination of both. According to Harvard’s Faculty Development and Diversity report, Harvard has decreased the percent of tenure offers going to women, with only 38% of external tenure offers going to women last year compared with 45% and 50% in years past. Women and men have equal rates of success in tenure review (68% for women, 69% for men), but only 65% of women stood for their review, compared with 78% of men, so only 45% of women achieve tenure compared with 54% of men.

Indeed, The Crimson found similar concerns with female faculty retention when it interviewed faculty and administrators in 2015.

What comes next for Harvard

Increasing the gender diversity of faculty at Harvard is a thorny, multifaceted issue, so there’s likely no silver bullet. Harvard will need to use several complementary, long-term strategies to start moving the needle on this problem. But, as we’ve found, one critical piece of the problem is improving the retention of female tenure-track faculty. Some solutions that Harvard faculty have proposed include reducing workplace hostility, improving mentorship, and stronger parental leave policies.

Harvard certainly has a lot of work to do to achieve gender balance among its faculty. But we think there are definite steps in the right direction that Harvard can take.

Limitations of our study

We acknowledge that our research isn’t perfect for a few reasons. For one, we double-counted faculty members in multiple departments. For instance, a professor of economics and government would be counted in both departments. Thus, our overall counts of professors may be incorrect — indeed, there were disparities between our counts and Harvard’s Faculty Development & Diversity report. Second, since we manually reviewed departments’ websites, our data will necessarily reflect any inaccuracies on the websites, plus any counting or tabulating errors we might have made.

In short, we might well have made mistakes. That’s just one of the reasons why we’re making our raw data and analysis public, as we always do. We encourage you to play around with this data and let us know if you find any errors or other interesting insights.

Keep an eye out for part two of this series investigating faculty diversity!